Who was this King Ashoka, also called Ashoka the Great? He was an extremely important figure on many levels, worldly and spiritual. His exact dates are unknown but it’s commonly thought that he lived from the 4th to 3rd century B.C.E. So he was born, in India, around 2,350 years ago. His name was Ashoka Morya.

Theosophists will recognise that name – Morya – as the mystical name of the mysterious Indian Guru of H. P. Blavatsky and who could be called the real, though usually unseen, Founder of the modern Theosophical Movement. This name is today usually transliterated as “Maurya” but in HPB’s time was written “Morya.” The Moryas are today a Rajput clan but for a time they ruled India, beginning with Ashoka’s grandfather, Chandragupta Morya. Ashoka thus came to rule the Mauryan Empire, which covered most of India. At his time, there was no country called India. That landmass consisted of numerous different kingdoms and republics, which functioned like separate nations. Ashoka brought almost all of them together and was therefore the creator of a unified India. It’s perhaps because of this that the symbol called the Ashoka Chakra or Ashoka Wheel is at the centre of the modern Indian flag.

Ashoka is famed for his dramatic conversion and transformation from a ruthless warlord to a man of profound peace, non-violence, and wisdom. This occurred after his victory in the Kalinga War, in which 100,000 of his opponents were killed and a further 150,000 forcibly deported. But on hearing a simple statement from the Buddha, recorded today in the Dhammapada, everything changed within him. Those words were: “Heedfulness is the path to the Deathless, heedlessness is the path to death. The heedful do not die, the heedless are already dead.”

He then became a Buddhist and is considered the first Buddhist emperor of India. His Buddhist teacher was the famed Vibhajjavada monk called Moggaliputta-Tissa. Vibhajjavada was the name at that time for what we today call Theravada Buddhism. In fact, in that era – a mere 200 years or less since the time of Buddha himself – the whole of Buddhism (then still confined to its native India) was Theravada-style. What is now known as Mahayana Buddhism was not yet in existence. Ashoka’s son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta became a Buddhist monk and nun and brought Buddhism to Sri Lanka. From Sri Lanka, Theravada – or the original Buddhist tradition – spread out to numerous other parts of Asia. With the post-Ashokan Hindu persecutions of Buddhism in India, and various other factors, Theravada Buddhism eventually made Sri Lanka its main base.

In “The Theosophical Glossary,” HPB summarises an intriguing point made in the anonymous article “Sakya Muni’s Place in History” from “Five Years of Theosophy.” These sources say that the records of Esoteric Buddhism report that it was Ashoka’s grandfather Chandragupta who was the convert to Buddhism and that Ashoka was thus a Buddhist from birth. They say though that he was not a heartfelt and serious Buddhist until into his adulthood, when he had his transformation.

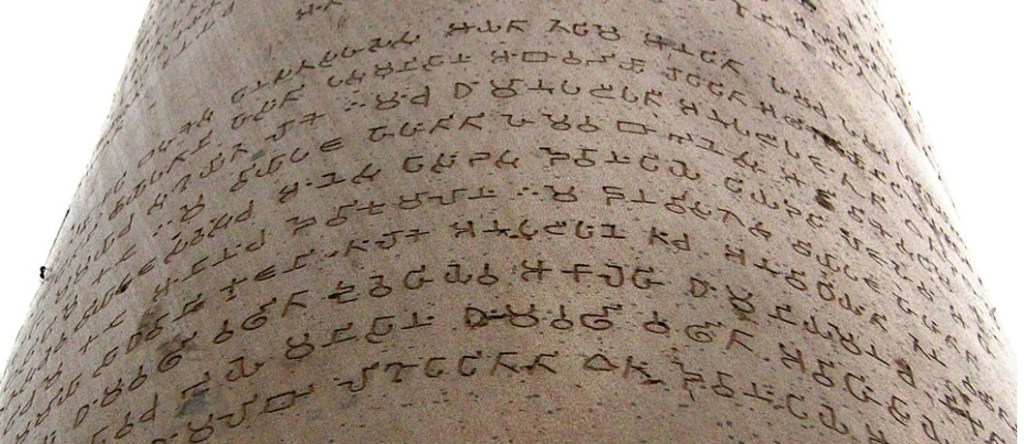

The word “edict” means “proclamation,” “decree,” or “ordinance.” Shortly, we’ll read selections from Ashoka’s famous Edicts (called Dhamma Edicts) that were erected across India and are still there today. HPB says that it was Chandragupta who began the practice of erecting these Edicts and that his grandson simply followed suit but intensified the effort. According to her, they were both known as Ashoka; Chandragupta was Kalashoka and his grandson was Dharmashoka. These details have not been substantiated by any historical evidence or research; perhaps they will be one day but in the meantime we can at least keep in mind that HPB firmly insists that these are the actual facts of the matter, as known to the Initiates and Masters.

As for the Dhamma or Dharma Edicts, one might assume that as a Buddhist, Ashoka was using this term simply as a synonym for the Buddhist doctrine, which adherents call “the Dharma.” But we’ll see that in the Edicts this word stands for the higher life or ethical, truth-based life. It does not carry sectarian connotations or mean exclusively the Buddhadharma, for the Edicts encourage an unsectarian, ecumenical, interfaith, universalist attitude towards all religions, while encouraging people to non-dogmatically adhere to their own chosen religion and to help it. We see exactly the same thing mirrored as one of the defining features of the Theosophical Movement of our times.

As with Gandhi, who also adopted this approach and championed non-violence, Ashoka is today a relentless target of criticism, derision, and deceptive propaganda by many orthodox and sectarian Hindus. If one searches on YouTube for Ashoka videos, the vast majority of the results are videos by Hindus – often young people – claiming that Ashoka was evil, a traitor to the “true religion,” and should not be given respect or importance. This is just a contemporary expression of the ancient opposition by orthodox and nationalistic Hinduism towards Buddhism. To quote from an online news article: “The formal denigration of Ashoka might be a recent affair. Yet it is the chiefly Brahminical conservatives who first started to invisibilise him [i.e. to erase his legacy and public awareness of it]. Their counter-reaction against Buddhism began just fifty years after he died. Ashoka’s ban on killing animals for ritual purposes had made Brahminical priests increasingly irrelevant while the spreading of Buddhism eroded the Varna [i.e. caste] system at its root. Ashoka’s grandson [the Emperor Brihadratha] was killed by Pushyamitra Shunga, his Brahmin military chief.”

This spelled the end of the Maurya Dynasty and India reverted to Hindu control, undoing the vast majority of Ashoka’s reforms.

In the article “Tibetan Teachings” and elsewhere, we read that Ashoka’s death effectively signalled the end of special stately protection for Buddhists and that the Hindu Brahmin priests promptly began their persecutions against Buddhism and especially the Buddhist Initiates, i.e. the proponents of the largely secret Esoteric Buddhism, prompting the latter to gradually leave India for safety in neighbouring Tibet, where – around Mount Kailash and other places – they sought refuge with the most ancient Esoteric School and eventually merged with it. That was the birth of the Trans-Himalayan Buddhist Esoteric School as we know it today, that sacred fraternity which would later bring the modern Theosophical Movement into being. H. P. Blavatsky writes regarding that exodus: “Then the Yogacharyā of Āryāsanga was merged into the oldest Lodge. For it is there from time immemorial that has lain concealed the final hope and light of the world, the salvation of mankind.”

Buddhist tradition says that after death, Ashoka was reborn as a serpent. This is taken literally by most Buddhists, as despite him being a hero of the faith, it is acknowledged that he would have to karmically atone for the many deaths and sufferings he caused prior to his transformation. But Theosophy enables us to see that in most cases, the serpent is an esoteric symbol of spiritual Wisdom, and that Buddhism’s references to nagas or serpent-beings are usually esoterically referring to human Initiates, i.e. Adepts or Masters of the Brotherhood. Perhaps, then, after the mortal man Ashoka Morya breathed his last, he became an Initiate or, if he was one already, rejoined that hidden esoteric Brotherhood that guides and watches over the spiritual evolution and advancement of humanity and whose sole aim and intent is TO BENEFIT MANKIND.

~ * ~

FROM THE FOURTEEN ROCK EDICTS

Here (in my domain) no living beings are to be slaughtered or offered in sacrifice. Formerly, in the kitchen of Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi [i.e. meaning “the humane king” or “king who regards all with kindness”], hundreds of thousands of animals were killed every day to make curry. But now with the writing of this Dhamma edict only three creatures, two peacocks and a deer are killed, and the deer not always. And in time, not even these three creatures will be killed.

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi’s domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Coḷas, the Pāṇḍyas, the Sātiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tāmraparṇī and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbours of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever roots or fruits are not available I have had them brought and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals.

In the past, for many hundreds of years, killing or harming living beings and improper behaviour towards relatives, and improper behaviour towards Brahmans and ascetics has increased. But now due to Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi’s Dhamma practice, the sound of the drum has been replaced by the sound of the Dhamma. The sighting of heavenly cars, auspicious elephants, bodies of fire and other divine sightings [i.e. various unusual phenomena that were seen in the sky by ordinary people following Ashoka’s transformation] has not happened for many hundreds of years. But now because Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi promotes restraint in the killing and harming of living beings, proper behaviour towards relatives, Brahmans and ascetics, and respect for mother, father and elders, such sightings have increased.

In the past there were no Dhamma Mahāmātras but such officers were appointed by me thirteen years after my coronation. Now they work among all religions for the establishment of Dhamma, for the promotion of Dhamma, and for the welfare and happiness of all who are devoted to Dhamma. . . . They work among soldiers, chiefs, Brahmans, householders, the poor, the aged and those devoted to Dhamma — for their welfare and happiness — so that they may be free from harassment. They (Dhamma Mahāmātras) work for the proper treatment of prisoners, towards their unfettering, and if the Mahāmātras think, “This one has a family to support,” “That one has been bewitched,” “This one is old,” then they work for the release of such prisoners. They work here, in outlying towns, in the women’s quarters belonging to my brothers and sisters, and among my other relatives. They are occupied everywhere. . . . This Dhamma edict has been written on stone so that it might endure long and that my descendants might act in conformity with it.

Truly, I consider the welfare of all to be my duty, and the root of this is exertion and the prompt despatch of business. There is no better work than promoting the welfare of all the people and whatever efforts I am making is to repay the debt I owe to all beings to assure their happiness in this life, and attain heaven in the next.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, desires that all religions should reside everywhere, for all of them desire self-control and purity of heart. But people have various desires and various passions, and they may practice all of what they should or only a part of it. But one who receives great gifts yet is lacking in self-control, purity of heart, gratitude and firm devotion, such a person is mean.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, honours both ascetics and the householders of all religions, and he honours them with gifts and honours of various kinds. But Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, does not value gifts and honours as much as he values this — that there should be growth in the essentials of all religions. Growth in essentials can be done in different ways, but all of them have as their root restraint in speech, that is, not praising one’s own religion, or condemning the religion of others without good cause. And if there is cause for criticism, it should be done in a mild way. But it is better to honour other religions for this reason. By so doing, one’s own religion benefits, and so do other religions, while doing otherwise harms one’s own religion and the religions of others. Whoever praises his own religion, due to excessive devotion, and condemns others with the thought “Let me glorify my own religion,” only harms his own religion. Therefore contact (between religions) is good.

One should listen to and respect the doctrines professed by others. Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, desires that all should be well-learned in the good doctrines of other religions. Those who are content with their own religion should be told this: Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, does not value gifts and honours as much as he values that there should be growth in the essentials of all religions. And to this end many are working — Dhamma Mahāmātras, Mahāmātras in charge of the women’s quarters, officers in charge of outlying areas, and other such officers. And the fruit of this is that one’s own religion grows and the Dhamma is illuminated also.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, conquered the Kāliṅgas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kāliṅgas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dhamma, a love for the Dhamma and for instruction in Dhamma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kāliṅgas. Indeed, Beloved-of-the-Gods is deeply pained by the killing, dying and deportation that take place when an unconquered country is conquered. . . . Now Beloved-of-the-Gods thinks that even those who do wrong should be forgiven where forgiveness is possible. . . . Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. . . .

I have had this Dhamma edict written so that my sons and great-grandsons may not consider making new conquests, or that if military conquests are made, that they be done with forbearance and light punishment, or better still, that they consider making conquest by Dhamma only, for that bears fruit in this world and the next. May all their intense devotion be given to this which has a result in this world and the next.

FROM THE KALINGA ROCK EDICTS

All men are my children. What I desire for my own children – and I desire their welfare and happiness both in this world and the next – that I desire for all men. You do not understand to what extent I desire this, and if some of you do understand, you do not understand the full extent of my desire.

I am telling you this so that I may discharge the debts I owe, and that in instructing you, that you may know that my vow and my promise will not be broken. Therefore acting in this way, you should perform your duties and assure them (the people beyond the borders) that: “The king is like a father. He feels towards us as he feels towards himself. We are to him like his own children.”

FROM THE MINOR ROCK EDICTS

Beloved-of-the-Gods speaks thus: It is now more than two and a half years since I became a lay-disciple [i.e. upasaka for a male, upasika if female; the term applied to any Buddhist who has both converted to the religion by “taking refuge in the Three Jewels” and committed to keep the Five Precepts: no killing, no stealing, no sexual misconduct, no lying, no intoxicants, i.e. alcohol or drugs], but until now I have not been very zealous. But now that I have visited the Sangha [i.e. the Buddhist monastic community] for more than a year, I have become very zealous. . . . This message has been proclaimed two hundred and fifty-six times by the king while on tour.

Father and mother should be respected and so should elders, kindness to living beings should be made strong and the truth should be spoken. In these ways, the Dhamma should be promoted. Likewise, a teacher should be honoured by his pupil and proper manners should be shown towards relations. This is an ancient rule that conduces to long life. Thus should one act.

Piyadasi, King of Magadha, saluting the Sangha and wishing them good health and happiness, speaks thus: You know, reverend sirs, how great my faith in the Buddha, the Dhamma and Sangha is. Whatever, reverend sirs, has been spoken by Lord Buddha, all that is well-spoken. I consider it proper, reverend sirs, to advise on how the good Dhamma should last long. These Dhamma texts — Extracts from the Discipline, the Noble Way of Life, the Fears to Come, the Poem on the Silent Sage, the Discourse on the Pure Life, Upatisa’s Questions, and the Advice to Rāhula which was spoken by the Buddha concerning false speech [Note: These have been identified as parts of the Anguttara Nikaya, Majjhima Nikaya, and Sutta Nipata, belonging to the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism] — these Dhamma texts, reverend sirs, I desire that all the monks and nuns may constantly listen to and remember [Note: Ashoka lived two centuries or so before the Buddha’s teachings were first committed to writing, but what was later written down as the Pali Canon had circulated among the monks, nuns, and devotees via an oral tradition established during Buddha’s own lifetime; it is known, for example, that large sections of the Sutta Nipata became known across India while Buddha was still alive]. Likewise the laymen and laywomen.

FROM THE SEVEN PILLAR EDICTS

And these are my instructions: to protect with Dhamma, to regulate with Dhamma, to make happiness through Dhamma and to guard with Dhamma.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, speaks thus: Dhamma is good, but what constitutes Dhamma? (It includes) little evil, much good, kindness, generosity, truthfulness and purity. I have given the gift of sight [Note: It is not known what this refers to; some think spiritual vision, while others propose it to be the ending of blinding as a form of punishment] in various ways. To two-footed and four-footed beings, to birds and aquatic animals, I have given various things including the gift of life [i.e. to “give the gift of life” in Buddhist terms means to purchase lots of animals that were intended for slaughter and then ceremonially release them into the wild].

Forests are not to be burnt either without reason or to kill creatures. One animal is not to be fed to another. . . . On the eighth of every fortnight [of the moon-cycle], on the fourteenth and fifteenth [day of the fortnight], on the day of the Tiṣya constellation, Punarvasu lunar mansion [i.e. nakshatra, all 27 of which play a fundamental role in Indian astrology], the three fourth-month days and other auspicious days, bulls are not to be castrated, billy goats, rams, boars and other animals that are usually castrated are not to be. On Tiṣya constellation days, Punarvasu lunar mansion day, the fourth-month full- and dark-moon day, horses and bullocks are not to be branded.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, says: Along roads I have had banyan trees planted so that they can give shade to animals and men, and I have had mango groves planted. At intervals of eight krośas, I have had wells dug, rest-houses built, and in various places, I have had watering-places made for the use of animals and men. But these are but minor achievements. . . . I have done these things for this purpose, that the people might practice the Dhamma.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, speaks thus: My Dhamma Mahāmātras too are occupied with various good works among the ascetics and householders of all religions. I have ordered that they should be occupied with the affairs of the Sangha [i.e. Buddhism]. I have also ordered that they should be occupied with the affairs of the Brahmans [i.e. Hinduism] and the Ājīvikas [i.e. a now long defunct Indian sect, based on absolute fatalism and the denial of the value of effort]. I have ordered that they be occupied with the Nigaṇṭhas [i.e. Jainism]. In fact, I have ordered that different Mahāmātras be occupied with the particular affairs of all different religions. . . . In my women’s quarters, they organise various charitable activities here and in the provinces. . . .

Whatever good deeds have been done by me, those the people accept and those they follow. Therefore they have progressed and will continue to progress by being respectful to mother and father, respectful to elders, by courtesy to the aged and proper behaviour towards Brahmans and ascetics, towards the poor and distressed, and even towards servants and employees. And I have given many other Dhamma regulations also. But it is by persuasion that progress among the people through Dhamma has had a greater effect in respect of harmlessness to living beings and non-killing of living beings. Concerning this, Beloved-of-the-Gods says: Wherever there are stone pillars or stone slabs, there this Dhamma edict is to be engraved so that it may long endure.

It has been engraved so that it may endure as long as my sons and great-grandsons live and as long as the sun and the moon shine, and so that people may practise it as instructed. For by practising it happiness will be attained in this world and the next.

(The above excerpts are quoted from “The Edicts of King Asoka,” translated by Ven. S. Dhammika, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka)

~ * ~

“A celebrated Indian king of the Môrya dynasty which reigned at Magadha. Asoka . . . was the most zealous supporter of Buddhism; he, who maintained in his palace from 60 to 70,000 monks and priests, who erected 84,000 totes and stupas throughout India, reigned 36 years, and sent missions to Ceylon [i.e. Sri Lanka], and throughout the world. The inscriptions of various edicts published by him display most noble ethical sentiments, . . . The sentiments are lofty and poetical, breathing tenderness for animals as well as men, and a lofty view of a king’s mission with regard to his people, that might be followed with great success in the present age of cruel wars and barbarous vivisection.” (H. P. Blavatsky, “The Theosophical Glossary” p. 36, Entry for “Asoka”)

“Three centuries B.C., in the great Empire of Asoka, the primacy of moral values was recognized in principle and practice. Is it not time to consider some of the fundamental teachings found in Asoka’s Edicts and to call the great Buddhist Emperor of ancient India in consultation for the erection of the new World State? For it can never stand if built on the competitive increase of armaments, which must inevitably lead to war. It can rest firmly only on the rock of tried and tested moral principles.

“Asoka’s chief concern was to promote Dharma, duty or the moral law, among his people. His Rock and Pillar Edicts set forth, in different languages of his time, the requirements of moral conduct in injunctions as valid today as when they were inscribed. . . . By the breadth of his religious tolerance no less than by the universality of his sympathies is Asoka fitted to be chosen as one of the architects of the new World State. . . . The spirit which animated his efforts is reflected in his Rock and Pillar Edicts, which breathe a universality as much needed by the modern world as are his abjuring of war and his preaching of non-violence towards living beings.” (B. P. Wadia, “Asoka’s Statesmanship,” “Thus Have I Heard” p. 32-34, also in “The Gandhian Way” under the title “What Does Dharma Include?”)

“In the Buddhist Mahavanso, Chandagatto, or Chandragupta, Asoka’s grandfather, is called a prince of the Moryan dynasty as he certainly was – or rather as they were, for there were several Chandraguptas. This dynasty, as said in the same book, began with certain Kshatriyas (warriors) of the Sakya line closely related to Gautama Buddha, who crossing the Himavanto (Himalayas) “discovered a delightful location, well watered, and situated in the midst of a forest of lofty bo and other trees. There they founded a town, which was called by its Sakya lords, Morya-Nagara.” Prof. Max Muller would see in this legend a made-up story . . . It was not the princes of Morya-Nagara who received their name from the Rajput tribe of Mori, but the latter that became so well known as being composed of the descendants of the Moryan sovereign of Morya-Nagara. . . . The words [of the Vishnu Purana]: “The Moryas will possess the earth, for Kautilya will place Chandragupta on the throne,” have in our occult philosophy a dual meaning. In one sense they relate to the days of early Buddhism, when a Chandragupta (Morya) was the king “of all the earth,” i.e., of Brahmans, who believed themselves the highest and only representatives of humanity for whom earth was evolved. The second meaning is purely esoteric. Every adept or genuine Mahatma is said to “possess the earth,” by the power of his occult knowledge. Hence, a series of ten Moryas, all initiated adepts, would be regarded by the occultists, and referred to as “possessing all the earth,” or all its knowledge. The names of “Chandragupta” and “Kautilya” have also an esoteric significance. Let our Brother ponder over their Sanskrit meaning, and he will perhaps see what bearing the phrase – “for Kautilya [i.e. literally meaning “crookedness,” “deceit,” “statecraft”] will place Chandragupta [i.e. literally “hidden/protected by the Moon”] upon the throne” – has upon the Moryas possessing the earth.” (H. P. Blavatsky, “The Puranas on the Dynasty of the Moryas and on Koothoomi,” “Five Years of Theosophy” p. 483-484)

~ * ~

THE FIRST EIGHT VERSES OF CHAPTER 2 (APPAMADAVAGGA)

OF THE DHAMMAPADA

It was hearing the first verse of this chapter that completely transformed the character of King Ashoka.

The title and subject of this chapter of the Dhammapada (the most well known collection of some of the Buddha’s practical psychological-ethical teachings) are translated as “heedfulness,” “vigilance,” “non-negligence,” and “diligence.” It refers to a sense of spiritual urgency and exertion, the realisation of the necessity of doing one’s utmost on the spiritual path in this lifetime and not shirking the needed effort.

1. Heedfulness is the path to the Deathless, heedlessness is the path to death. The heedful do not die, the heedless are already dead.

2. Clearly understanding this excellence of heedfulness, the wise exult therein and enjoy the resort of the noble ones.

3. The wise ones, ever meditative and steadfastly persevering, experience Nibbana, the incomparable freedom from bondage.

4. Ever grows the glory of one who is energetic, mindful, and pure in conduct, discerning and self-controlled, righteous and heedful.

5. By effort and heedfulness, discipline and self-mastery, let the wise one make for himself an island which no flood can overwhelm.

6. The foolish and ignorant indulge in heedlessness, but the wise one guards heedfulness as his best treasure.

7. Do not give way to heedlessness; do not indulge in sensual pleasures. Only the heedful and meditative attain great happiness.

8. Just as one upon the summit of a mountain beholds the groundlings, even so when the wise man casts away heedlessness by heedfulness and ascends the high tower of wisdom, this sorrowless sage beholds the sorrowing and foolish multitude.

(Translation by Acharya Buddharakkhita, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka)

~ * ~

This article may have raised more questions about various things. Please make use of the site search function (the magnifying glass symbol at the top of the page) and visit the Articles page to see the complete list of over 400 articles covering all aspects of Theosophy and the Theosophical Movement. You may find the articles linked to in this present article of particular usefulness, as also those listed on the Articles page under the headings “BUDDHISM” and “THE MASTERS.” The article Ethics: The Soul of The Wisdom-Religion explains how and why ethics are the most important aspect of Theosophy and of its Message for the modern world.

~ BlavatskyTheosophy.com ~